Printing in Mexico, which had such a brilliant start in the 16th century, continued to grow no less flourishing in the following centuries. The Old styles letter called «de Tortis», that made the books of that century so similar to European «incunables», disappeared to make room for the Roman type, so common all over the world. At times, in attempt to imitate Italy, italic type was used throughout in a book, although this was not usually the case.

At the beginning of 1600, covers were simple, of beautiful lines and well proportioned. Gradually they became more complicated, as writing contributed to make them more confusing; it may be said that with other art, expressions had accordingly transformed into «baroque» style.

Wood engraving continues, only to illustrate cheap wotks and for ornamentation of book covers in form of coat-of-arms, cornices, capitals and endings. The fine illustrations were engraven in copper sheets by native or European craftsmen and although their technique is far from perfect, they represent a suggestive outlook. They were used to engrave covers, pictures, allegories or to illustrate the work of map copying, or tombstones or scenes described therein. Books with copper and wood engravings are frequent. Typographic value of the works printed in the 17th century, as such, is very questionable, there being only a few that can be considered well done. Defective type, poorly lined, unevenly printed due to poor quality of paper, with ink that sometines changes its hue and other times excessive use of it make the reading hard. So are these old and attractive books.

When a Woman printer, Doña María de Rivera, widow of the famous Bernardo Calderón, opened in 1687 a new printing shop in Antwerp, we hoped to find books as perfect as those of the Plantin style, but our disappointment was hopeless. We must remember, though, printers that flourished in the 17th century; engravers who illustrated their works, that is to say; the most important books they made. It should not be overlooked that printing is a means of spreading human knowledge.

The foremost printers of the 17th century are: Henry Martin, a well-learned man, linguist, surveyor and astronomer. It was he who marked the site of drain in Mexico with an astonishing accuracy. Although he was far from lucky, posterity made him justice. His tasks as printer comprise from 1599 to 1611, having published wonderful books, among them his own «Reportorio de los Tiempos» (Report of the Times). Next come Diego Lópes Dávalos, who flourished from 1601 to 1615, and the Flemish Cornelio Adriano César, a victim of the Inquisition (1602-1633). Juan Ruiz continued the tradition and he and his heirs toiled from 1613 to 1678. Juan Blanco de Alcázar shines only six years (1620-1626) and Francisco Rodríguez Lupercio, who beagn in 1658 and whose printing shop was closed after being managed by his widow and heirs in 1736. Guillena Carrascoso (1684-1700) and his heirs, from 1708 to 1721 and las a short famed printer Diego Fernández de León, who worked only from 1690 to 1692 moving his shop later to Puebla.

These were the foremost printers as second and third raters are a crowd. Those who desire to know them better only have to look at the wonderful «Imprenta en México» (Printing in Mexico) by Don José Toribio Medina, almost unfailing in this short of investigation.

Most famous engravers in copper in the 17th century are Samuel Estradamus of Antwerp, who flourished from 1604 to 1623; Antonio Castro from 1666 to 1740; the engraver of «Llanto del Occidente» (Weeping of the West), 1666, Vicente Espejo, who did some engraving in 1677; Rosillo who worked from 1679 to 1733; Francisco de Torres, whose name is found in books in 1688 and Antonio Isarti, perhaps the greatest. His work fills the end of the century, from 1681.

The first book printed in the 17th century is written in the Mexican Language. Its title is «Huehuetlatolli». It is a gathering of moral advice by parents to their children. The book was published by Fr. Juan Bautista in the printing shop of the college of Santiago Tlatelolco, were indians learnt the art of printing. As the only known copy is incomplete, this point is not well proved but what is certain is that Fr. Olmos translated these conversations into spanish and gave them to the celebrated Fr. Bartolomé de las Casas, who included them in his «Historia Apologética de las Indias» (An Apologetic History of the Indies).

The chief books printed in Mexico during the 17th century may be gruped as follows:

1. Books realting to the indian languages

2. Religious chronicles and History books

3. Religious works, sermons lives of the Saints and Friars

4. Scientific Works

5. Literary Works

6. Periodical publications

Books dealing with indian languages of Mexico are not so numerous as in the 16th century, but they are still published. The greatest number appeared from 1601 to 1649, that is to say, in the first half of the century. In the remaining years only a few came out. Naturally the most patronized language is Mexican and from the time of the «Huehuetlatolli» quoted above works became more numerous.

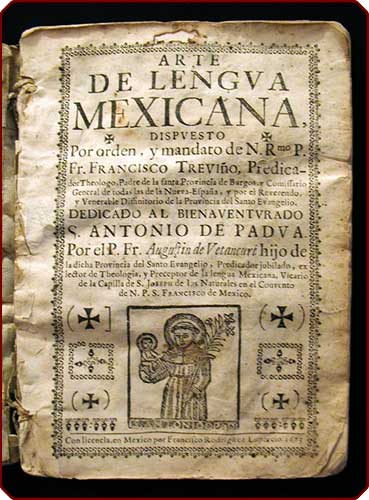

Mijangos with this «Espejo Divino» (Divine Mirror), 1607 and his «Sermonario» (Sermon Book), 1624; Arenas with this «Vocabulario» (Vocabulary) many times reprinted from the beginning of 1611 ; León, with this «Camino del Cielo» (Way so Heaven), 1611, and his «Sermonario» (Sermon Book) 1614; Alva, with his «Confesionario» (Confession Book), 1634; Castillo, with his «Cartilla Mayor» (Elder Primer) of which nothing but the edition of 1683 is known but which existed a long time before, and Galdo Guzmán (1642), Carochi (1645), Vetancourt (1673) and Guerra (1692) with their «Artes» (Arts), continued the tradition of the Náhoa linguists. The remaining languages have few partisans, the Zapotec, one Grammar (1607) by Cueva; the Timucuana language, the «Catechism» (1612) by Pareja; the Mayan, «The Doctrine» (1629) by Nájera; the Mame, an «Art and Vocabulary» (1644) by Reynoso, and the Tarasco, «The Catechism» by Fr. Bartolomé Cataño, translated into that language by Fr. Angel Sera, and published in this century on an unknown date.

During the 17th century the chronicles of the religious orders began to appear, becoming invaluable sources for the history of Mexico.

Printed in this country are the Augustines chronicles by González de la Puente (1624), Grijalva (1624) and Basalanque (1673); the Franciscans´by La Rea (1643), the beatiful works of Vetancourt «Cronica» (1697) and «Teatro» (1698) and Medina´s for the province of San Diego (1682). The Dominicans have the chronicles Burgoa for the province of Oaxaca with this works «Palestra Historial» (Historial Arena), 1670, and «Geográfica Descripción» (Geographical Description), 1674, and the Jesuits the chronicle of Fr. Florencia (1694).

The remaining historical works are not numerous. There are «Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas» (Events of the Phillipine Islands), by Morga (1609); «Relaciones acerca de la monja Alférez» (An account about the «Lieutenant Nun»), 1653; those about «Autos de Fe» for a number of years; the «Sucesos de Fr. García Guerra» by Mateo Alemán (1613); the «Llanto del Occidente» (Weeping of the West) by Sariñana, narrative of the burial of Phillip IV (1666); «Noticia Breve de la Dedicación de la Catedral de México» (A brief Account of the Dedication of Mexico´s Cathedral), 1668, of the same author and many more small ones various subjects.

Religious books are numerous. A number of sermons, lives of Saints and Friars or Monks, prayers and «novenas» (nine days devotions) nearly fill up two volumes of the works of Medina. We quote as the most important of the Guadalupian writers: Sanchez (1648), Laso de la Vega (1649), Becerra Tanco (1666) and Florencia (1688); also, Cisneros, with his work on the «Virgen de los Remedios» (The Virgin of Remedies), 1621, and Arce, with his «Prójimo Evangélico» (The Evangelican Neighbors), 1651, a biography of Bernardino Alvarez.

Scientific works are scarce. Henry Martin, printer, spoken of above, published in his own shop his «Reportorio de los Tiempos» (Report of the Times), 1606. Echave studied the Basque language (1607) and Mateo Alemán the celebrated author of the «Guzmán Alfarache», produced a new «Ortografía Castellana» (Castilian Orthography), 1609, which he only used in some of his latest works.

In 1610 «Tratado Breve de Medicina» (Brief Treaty of Medicine), by Fr. Agustin Farfán was reprinted and in 1615 came to light the «Cuatro libros de la Naturaleza» (Four Books of Nature), by Fr. Francisco Jiménez, in which is contained a translation of the famous work of Dr. Hernández, a good deal of information being added to it.

The City of Mexico, scourged by floods, was the cause of two remarkable books: «Sitio de la ciudad de México» (The Siege of the City of Mexico), by Cisneros (1618) and another of the same title by Cepeda y Carrillo (1657). Finally, the jesuit Kino published in 1681 «Exposición Filosófica contra el cometa» (Philosophical Exposition against the Comet) bearing on the comet which had appeared then, his work provoking a curious controversy in which the famous Don Carlos Sigüenza y Góngora was the champion.

Literary works of an amusing form were few and almost to the last one with fixed purpose in mind. We will cite «Grandeza Mexicana» (Mexican Greatness), 1604, by Bernardo de Balbuena; «Coloquios Espirituales» (Spiritual colloquies), 1610, by Fernán González de Eslava; «Los Sirgueros de la Virgen» (The Haulers of the Virgin), 1620, by Bramán; » Obediencia que Mexico…» (Obeyance that Mexico…) by Arias de Villalobos, published in 1623, including «Canto Intitulado Mercurio» (The Chant called Mercury), describing Mexico City in 1603, addressed to Viceroy Montesclaros on his entering the City.

Most remarkable literary works published in Mexico during that century are those of Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, the poligrapher cited above. His first book was «Primavera Indiana» (Indian Springtime), 1688, which was followed by «Glorias de Queretaro» (Glory of Querétaro), 1680; «Teatro de Virtudes Políticas» (Theater of Political Virutes), 1680; «Panegírico», when Conde de Paredes entered the City (1680); «Manifiesto filosófico contra cometas» (Philosophical Manifest against comets), 1681; «Triunfo Partánico» (Parthenon Triumph), 1683; «Paraíso Occidental» (Western Paradise), 1684; «Infortunios de Alonso Ramírez» (Misfortunes of Alonso Ramírez), 1690; «Libra Astronómica» (Astronomical Pound), 1690; «Trofeo de la Justicia Española» (Trophy of Spanish Justice), 1691; » Mercurio Volante» (Flying Mercury), 1693; «Oriental Planeta Evagélico» (Evangelical Oriental Planet), 1700; one of his most remarkable works, «Piedad Heroica de Don Fernando Cortés» (Heroic Piety of Don Fernando Cortés) is not complete, for which reason its printing date is unknown.

We will have to cite also Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, the great Mexican poetress. Although her complete works were published in the spanish capital, in 1673 come «Villancicos» appeared in the viceregal capital, in 1680, her «Neptuno Alegórico» (Allegorical Neptune) a description of the arch erected by the Cathedral for the entrance of Coinde Paredes; in 1690, her sacramental pledge «El Divino Narciso» (The divine Narcissus) and or an unknown date some «Ofrecimientos del Rosario» (Offerings of the Rosary).

To the 17th century credit is due for at that period started the publishing of periodicals, although theses did not have the character they acquired later. The first «Gaceta» (Gazette) to appear in Mexico was brought out in 1671 and was printed in the shop of Bernardino Calderón. His widow, Doña María de Rivera, went ahead with it until 1687. In the following century it began to appear more often, being, by then, of great help to the community.

In 1722 it was issued by Don Juan Ignacio de Castorena Ursúa and from 1728, Don Juan Francisco de Sahagún de Arévalo, was in charge of it. They were the real founders of Mexican newspaper era.

By this report the intense cultural life of Spain´s favorite colony during the 17th century can be appreciated, printing being its most helpful divulger.

El texto fue publicado originalmente en la revista Mexican Art & Life No.7 en julio de 1939 en los Talleres Gráficos de la Nación

I am an historian, and i aprecciate the quality of information and your freedom. :)

Memo