Undoubtedly patronized by Fray de Zumárraga, Bishop of Mexico (who by the way labored enthusiastically to bring printing to Mexico), Pablos opened his workshop in a section of the Episcopal Palace. This place was known as the House of Bells, because bells were casted here for the different churches of the diocese of Mexico. It did not take long to organize the print shop, as towards the end of 1539, the first printed book was published. Its title is «Breve y mas compendiosa Doctrina Cristiana en lengua Mexicana y Castellana…» (A short and abridged Christian Doctrine in the Mexican and Spanish languages…) In its colophon we are told that the book was printed at the expense of Zumárraga «in the great City of Tenuchtitlán-México… in the shop of John Cromberger, in the year one thousand five hundred and thirty nine».

Even if it may be called a book, it really is a quarto-sized pamphlet of twelve pages, printed in the gothic type. Unfortunately the only known specimen is lost.

After this first publication other books of the same religious item soon followed. It must be understood that the Church by then, -engaged in preaching the Gospel- was the most important client of printing shops. The Church needed, therefore, a good deal of elementary text books, such as doctrine booklets, catechisms, rules for processions, confession books and so forth. Occasionally, other subjects were picked up and so a detailed information of the terrible earthquake of Guatemala, due to the eruption of a volcano, describes the catastrophe suffered by that city.

Later on, when the printing industry was developed either by enlargement of the first shop or the establishment of better equipped ones like that Antonio de Espinosa in 1559, printed matter improved very much in quality. During this stage of prosperity, valuable books on liturgy (missals, anthem-books, prayer-books, ritual books, Passion Books, hand-books of the holy sacraments and choir-books) were produced, which for their quality and fineness may well stand comparison with European works published by Plantin, the Giunta brothers and Andrea de Portonaris.

It is indeed gratifying to note that the early Mexican press produced books of modern scientific value. Time has not yet been able to tarnish the vocabularies, grammars and dictionaries written by the missionaries in almost all of the native languages and dialects. They give us important historical, ethnographic and linguistic information about Náhoas, Mayas, Mixtecs, Zapotecs, Mixes, Chuchonas, Otomíes, Huastecas, Tarascos, Totonacs, etc. They are valuable reference books for studying the past of these tribes, now very much decayed or transformed. Along with the study of the structure of the strange tongues, chronologic and geographic data were obtained, which enable modern scholars to work upon trustworthy material, sometimes the only one available concerning gone-by civilizations.

The capital of New Spain was in no way inferior to its metropolis as to culture and refinement, nor did it remain behind as to the general European evolution. Good examples of this forwardness in the field of philosophical currents are the books of Fray Alonso de la Veracruz, founder of the first University of America. His philosophical works are equal to any such texts produced during the period on the other side of the Atlantic. Medical science had a number of learned treatises on surgery, anatomy, apothecary files, formularies and pharmacopeias written by Fray Agustín Farfán former physician of Phillip II, by Dr. López de Hinojosos and by Dr. Juan Bravo. In this short of activity the native empirical practitioners -very skilled in their work- from the Imperial College of Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, handed out very valuable cooperation.

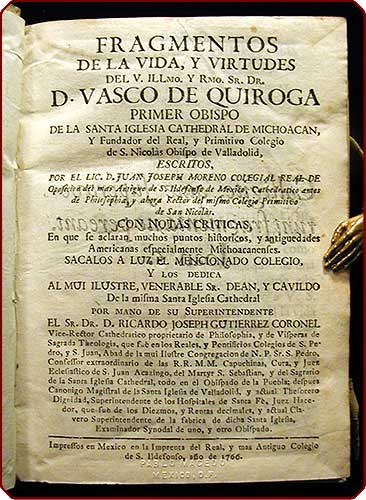

Another important set of early books is the compilation of law subjects and legislation by Doctor Vasco de Puga as well as the Synodal Constitutions of the Archbishopric of Mexico, the numerous religious acts, monastic rules, hospital constitutions, decrees, papal bulls and ordinances.

Under the general item of humanist arts and sciences, we should mention the works of the previously cited Fray Alonso de la Veracruz, of Doctor Cervantes de Salazar and Doctor Cárdenas. Furthermore, there are the Arithmetics by Juan Díaz Freile, the nautical and military works by Doctor Diego García de Palacio, and a number of essays about logics, religious oratory and poetry. Greek and Latin classics with commentaries (Ovid, Virgil, Martial, Terence, Aristotle, Plato, Juvenal, Seneca, etc.) were also published and profusely divulgated by the Jesuits, who used them as text-books in their colleges and seminaries. A vast, interesting literature which dealt with a great many trilling subjects and cases and related to the mythical beliefs and superstitions of the Indians, is offered by the theological studies.

Referring to the Indians, we must say that the pupils of the College of Tlatelolco cooperated with this cultural development, contributing with material aid to the printing of the books, or translating sacred texts, sermons, lives of Saints and even European religious plays into their native dialects. Fray Juan Bautista renders a well deserved homage to the Indians of this college, by giving us the list of their names.

A truly wealthy, substantial and efficient production was yielded in the 16th Century by the early press in New Spain. These primitive books are not -by any means- rare and exquisite bibliographic oddities. They represent -on the contrary- a genuine collective effort, contributing to raise the actual standard of human thought and culture.

The present study must not conclude without referring to the material appearance of the first books printed in Mexico, books which are erroneously called «incunabula». Incunables are those books which the early typographic art produced in the 15th Century. The books printed in Mexico in the early decades after the Conquest, belong to a period of splendor which differs essentially form the modest productions achieved by the incipient graphic arts.

According to the printing fashion in vogue at that time, the paper of our Mexicans editions was of a beautiful, thick quality, wrought with filigrees and watermarks. It was usually printed with Gothic type and Arabian numbers to mark down the pages. It is not infrequent, therefore, to find books with Roman and semi-Gothic types, the latter commonly called «tortis» largely used in the best Italian editions. At the foot of the pages, the register of the editions was marked according to the sheets, a cross or an asterisk (*) being used for the preliminary pages, and the letters of the alphabet, followed by ordinal numbers, for the current text. These marks, as a rule, only appeared on half of the pages of every sheet. The editor’s name or the shop in which the book was made usually was printed on the title page, and it also was always printed on the last page, in the colophon that also contained the name of the person who defrayed the expense of the edition, and the day, month and year in which it was finished.

Following the Spanish printing fashion, it was customary to print the pages at full width, but when native languages or dialects were published, the text was spread in two columns. As to the size of the book the term folio was used to designate a sheet, doubled in half to make two pages, this doubled again gave the quarto size; and again doubled gave the octavo size, and henceforth in the same manner.

Cromberger, and Juan Pablos after him, did not use any special trade mark for their editions, but later on, Antonio de Espinosa (1559-1576) employed a coat of arms to distinguish his valuable books.

Cathecisms, doctrine books and others were decorated with engravings and vignettes most of them in woodcuts; a few on mystical subjects were engraved on lead plates. The majority of the books were binded in handy flexible parchment. Leather was also used, and even de luxe bindings were pproduced with golden stampings and brass lockets. The parchment binding usually had leather straps fixed on the edges as practical closing devices.

Illuminations being no longer applied to books, in view of the fact that the initials were now printed, it became the custom, principally among the monks, to decorate the front edges of the books with ink. On the back, the abbreviated title was written with large thick letters.

During this period, «Ex-libris» were not yet in use, but many a book-owner, including friars, took pleasure in writing their name on the upper cover of the book, adding at times such statements as: «…this book is for the use of Fray… by special permission of his Superior».

The foregoing is a brief sketch of Mexico’s contribution to the world history of typographic achievements. By joining the group of outstanding nations, which have been able to maintain a real tradition of high culture, Mexico has given a fine example of its capacity and intellectuality.

La imagen fue tomada del sitio: Philadelphia Rare Books and Manuscripts

El texto fue publicado originalmente en la revista Mexican Art & Life No.7 en julio de 1939 en los Talleres Gráficos de la Nación

Debe estar conectado para enviar un comentario.